권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title Page

Contents

Abstract 26

Chapter Ⅰ. Introduction 28

1-1. Introduction to van der Waals layered materials 28

1-1-1. Crystal structures of van der Waals layered materials 30

1-1-2. Electrical properties of van der Waals layered materials 38

1-1-3. 2D van der Waals heterostructures 44

1-2. Introduction to magnetic properties 44

1-2-1. The origin of magnetism; a theoretical background 45

1-2-2. Diamagnetism and paramagnetism 48

1-2-3. Ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism 50

1-2-4. Paramagnetic ions and crystal field theory 53

1-3. Magnetic interactions 55

1-3-1. Magnetic dipolar interaction energy 56

1-3-2. Direct exchange 57

1-3-3. Superexchange 60

1-3-4. Indirect exchange 62

1-3-5. Antisymmetric exchange 62

1-3-6. Itinerant exchange 64

1-4. Magnetism in 2D van der Waals materials 66

1-4-1. Intrinsic 2D vdW magnets 67

1-4-2. Extrinsic 2D vdW magnets 69

1-4-3. Doping-induced magnetism 69

1-4-4. TMD-based DMSs 70

1-4-5. Synergetic proximity effect at 2D vdW heterostructures 71

1-4-6. Spintronic applications in Fe₃GeTe₂-based 2D vdW heterostructures 74

Chapter Ⅱ. High-mobility junction field-effect transistor via graphene/MoS₂ heterointerface 76

2-1. Introduction 77

2-2. Experimental methods 79

2-2-1. Material synthesis 79

2-2-2. Device fabrication 80

2-2-3. Optical and electrical characterization 81

2-3. Results and discussion 82

2-3-1. Schematic illustration, Raman characterization and band diagram of the heterostructure 82

2-3-2. Electrical properties at non-overlapped graphene/MoS₂ structure 85

2-3-3. Electrical properties at overlapped graphene/MoS₂ structure 91

2-3-4. Schottky barrier height estimation at graphene/MoS₂ heterointerfaces 94

2-4. Conclusion 100

Chapter Ⅲ. Proximity-induced tunable magnetic order at the interface of all-van der Waals-layered heterostructures 102

3-1. Introduction 103

3-2. Experimental methods 107

3-2-1. Synthesis of W₁₋ₓVₓSe₂ monolayer 107

3-2-2. Device fabrication process 107

3-2-3. Measurements of Hall resistance 108

3-3. Results and discussion 109

3-3-1. Structural properties of the FGT/W₁₋ₓVₓSe₂ devices 109

3-3-2. Electrical measurements of a monolayer W₁₋ₓVₓSe₂ flake 112

3-3-3. Diverse magnetic phases in the heterostructure devices 113

3-3-4. H-T Phase diagram derived from coercivity extraction. 121

3-3-5. Different magnetization switching behavior by different SOC strength 128

3-3-6. Interfacial proximity effect in an inverted heterostructure 133

3-3-7. Sample stability issue during/after measurements 136

3-4. Conclusion 137

References 140

국문초록 158

Figure 1-1. Carbon allotropes. 31

Figure 1-2. The periodic table for a list of transition metal and chalcogen elements for TMD formation. 34

Figure 1-3. The different 3 phases of MoS₂ monolayer. 36

Figure 1-4. The atomic structure of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN). 37

Figure 1-5. The band structure of graphene and its ultra-high carrier mobility. 39

Figure 1-6. The substrate effect on the 2D materials. 41

Figure 1-7. Band gap of TMDs and dependence on the number of layers. 42

Figure 1-8. Band gap spectrum in van der Waals layered materials 43

Figure 1-9. Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility in paramagnets, ferromagnets, and antiferromagnets. 52

Figure 1-10. The schematic illustration of crystal splitting of d-orbitals of a paramagnetic TM ion. 54

Figure 1-11. The spatially symmetric and antisymmetric wave functions for the H₂ molecule depending on the interatom distance. 58

Figure 1-12. The energy splitting of the spin singlet and spin triplet states for the H₂ molecule. The sign of the exchange integral J is negative, so the singlet... 59

Figure 1-13. Spin ordering in ferromagnets (J>0) and antiferromagnets (J<0) 60

Figure 1-14. An example of typical superexchange bond in the Mn²⁺-O²⁻-Mn²⁺ system. 61

Figure 1-15. The schematic illustration of DMI in a system with large SOC. 63

Figure 1-16. RKKY exchange interaction for Mn atoms as a function of interatomic distance in Mn₂Ge₆₂. 64

Figure 1-17. Schematic representation of direct, indirect, superexchange, RKKY, and DMI. 65

Figure 1-18. The library of intrinsic van der Waals magnets. 68

Figure 1-19. Schematic illustration of inserting adatoms into nonmagnetic semiconductors for inducing ferromagnetism. 70

Figure 1-20. Interfacial engineering of 2D magnet interfaces. 73

Figure 2-1. A schematic illustration of Gr/MoS₂ heterostructure device. 82

Figure 2-2. Energy diagram at the Gr/MoS₂ heterointerface and carrier transfer direction. 83

Figure 2-3. Raman spectroscopy of Gr/MoS₂ heterojunction device. 84

Figure 2-4. Electrical characteristics of Gr/MoS₂ heterostructure device, device#1 and device #2. 86

Figure 2-5. Pure MoS₂ device for comparison and overall device characteristics compared in a single plot. 90

Figure 2-6. The overlapping device (Device #3) and its IDS-VBG characteristics.[이미지참조] 92

Figure 2-7. The comparison of individual device characteristics and model for direct tunneling at the overlapped device (Device #3). 93

Figure 2-8. Determination of y-intercept for SBH calculation. 95

Figure 2-9. The IDS-VDS extracted for SBH calculation and energy diagram schematic of the structure of Device #4.[이미지참조] 96

Figure 2-10. Determination of y-intercept for Device #3 SBH calculation. 97

Figure 2-11. The IDS-VDS extracted for SBH calculation and energy diagram schematic of the structure of Device #3.[이미지참조] 98

Figure 2-12. Estimated Schottky barrier height at Gr/MoS₂ heterointerface. 100

Figure 3-1. Device schematic and corresponding optical microscopic image. 109

Figure 3-2. The optical microscopy (upper panel) and atomic force microscopy (lower panel) images of devices. 110

Figure 3-3. Crystal structures of each sample and their temperature dependent Rₓₓ measurement results. 111

Figure 3-4. Electrical characteristics of W₁₋ₓVₓSe₂ monolayer devices. 112

Figure 3-5. Temperature-dependent Rxy(μ₀H) after the offset subtraction by anti-symmetrization.[이미지참조] 114

Figure 3-6. The representative Rxy(μ₀H) data for all devices at 2, 120, 180,and 200 K for comparison.[이미지참조] 115

Figure 3-7. Deconvolution of Rxy(μ₀H) data at various temperatures below Tc.[이미지참조] 118

Figure 3-8. Temperature-dependent Hall resistance Rxy(μ₀H) for FGT/o-FGT(yellow dots), FGT/W₀.₀₉V₀.₀₅Se₂ (green dots) and FGT/WSe₂ heterostructure...[이미지참조] 119

Figure 3-9. Determination of Rxy,0T and HC from the measured data in FGT/W₀.₉₅V₀.₀₅Se₂ at 100K.[이미지참조] 122

Figure 3-10. Field-derivative of Rxy for FGT, FGT/W₀.₉₅V₀.₀₅Se₂, and FGT/WSe₂ at various temperatures.[이미지참조] 123

Figure 3-11. Rxy,0T-T phase diagram of each device.[이미지참조] 124

Figure 3-12. Magnetic diagram for whole measuring temperature region. 126

Figure 3-13. Interlayer exchange coupling and witching behavior at T=150 K. 128

Figure 3-14. Schematic diagram of expected magnetic order at the interface upon SOC strength with spin-flop, spin-flip, and spin-flip and inverted magnetization. 130

Figure 3-15. Field-derivative of Rxy(μ₀H) and magnetic switching speed.[이미지참조] 131

Figure 3-16. Inverted W₀.₉₅V₀.₀₅Se₂/FGT heterostructure device with the bottomelectrodes and Temperature-dependent Rₓₓ. 133

Figure 3-17. Temperature-dependent Rxy(μ₀H) for W₀.₉₅V₀.₀₅Se₂/FGT after subtracting the offset by anti-symmetrization.[이미지참조] 134

Figure 3-18. Rxy(μ₀H) for the inverted devices.[이미지참조] 135

Figure 3-19. The time-dependent measurement of the W₀.₉₅V₀.₀₅Se₂/FGT heterostructure sample. 136

이차원 판데르발스 (van der Waals) 층상물질은 최근 광범위한 관심과 함께 미래의 유망한 전자 및 자기재료로서 각광받고 있다. 2004 년 그래핀의 발견은 그 특이한 전기적, 열적, 기계적, 그리고 광학적 특성으로 인하여 저차원물질기반 물리학이라는 분야에 일대 변혁을 불러일으켰다. 그래핀의 성공으로 학자들은 자연스럽게 반도체성을 지닌 전이금속 디칼코겐화물(TMD)과 절연성을 지닌 육방정계 질화 붕소라는 새로운 이차원 판데르발스 물질을 찾아내기에 이른다. 그 중 TMD 는 그래핀에는 존재하지 않는 밴드갭 에너지를 가지므로 이차원 물질을 기반으로 한 전자 소자와 광전자 소자에 널리 응용되고 있다. 그 후, 물리학자들은 마침내 자기적 특성을 지닌 이차원 판데르발스 물질을 발견하였다. 이러한 물질군은 외부에서 인가된 자기장의 방향에 대하여 전자의 스핀이 정렬됨에 따라 강자성, 반강자성 등을 보이는데 이를 이차원 자성체라 칭한다. 이들 판데르발스 물질의 흥미로운 특성들 중 하나는 계면에서 관찰되는 현상이다. 기존의 전통적인 삼차원 물질로는 격자부정합 때문에 이종접합구조의 물질 선정에 있어서 자유도가 떨어졌던 것이 사실이다. 반면에, 이차원 판데르발스 물질을 활용하면 계면에서 자연적으로 형성되는 판데르발스 갭에 의하여 이러한 문제가 개선되어 이종접합구조의 물질 선정과 조합이 비교적 자유롭다. 그러므로 많은 흥미로운 전기적, 그리고 자기적 특성에 대한 고찰들이 여러 종류의 이차원 판데르발스 물질을 결합함으로써 가능하였다.

본 논문에서는 적절한 이차원 물질들을 선정함으로써 이종접합구조를 구현하고 그 계면에서 일어나는 전기적, 자기적 현상에 대한 관찰과 해석을 제시한다. 첫번째로 그래핀과 n-형 이황화몰리브데늄 (MoS₂)을 활용하여 높은 전하이동도와 스위칭 성능을 동시에 지니는 전자소자를 성공적으로 구현하였다. 이러한 전기적 특성은 MoS₂ 와 게이트전압에 의한 전기적 극성 변환이 가능한 그래핀 채널의 계면에서 형성되는 쇼트키 장벽 높이를 조절함으로써 얻어지는 것을 확인하였다. 다음으로는 금속성 강자성체인 Fe₃GeTe₂ (FGT)와 바나듐 (V)에 의하여 도핑되거나 혹은 도핑되지 않은 단일층 다이셀레나이드텅스텐 (WSe₂)을 활용한 이종접합소자를 구현하여 해당 계면에서 관찰되는 자기적 특성에 대하여 고찰하였다. FGT 에서 비롯된 강자성은 FGT 단독으로 쓰일 때 보다 FGT 와 WSe₂ 를 결합하였을 때 더 높은 온도에서 그 특성인 보자력과 잔류 자기모멘트가 유지됨을 확인하였다. 그리고 이러한 접합구조의 계면에서 다양한 자기적 현상인 스핀-플롭, 스핀-플립, 그리고 역방향 자화변화가 나타남을 확인하였다. 이러한 자기적 특성들은 각 물질의 서로 다른 스핀-궤도 결합기인 인접효과에 의한 것으로 확인되었으며 이것은 바나듐의 도핑농도에 따라 조절가능한 스핀-궤도 결합의 세기가 장범위 자기질서도에 영향을 미치는 자기결정이방성을 변화시키기 때문인 것으로 확인되었다. 또한 FGT 와 바나듐으로 도핑된 WSe₂ 를 접합한 이종접합소자에서 합성형 반자성체의 거동을 구현하였는데 이는 자성 인접 효과에 기인한 것으로 확인되었다.*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| 전화번호 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

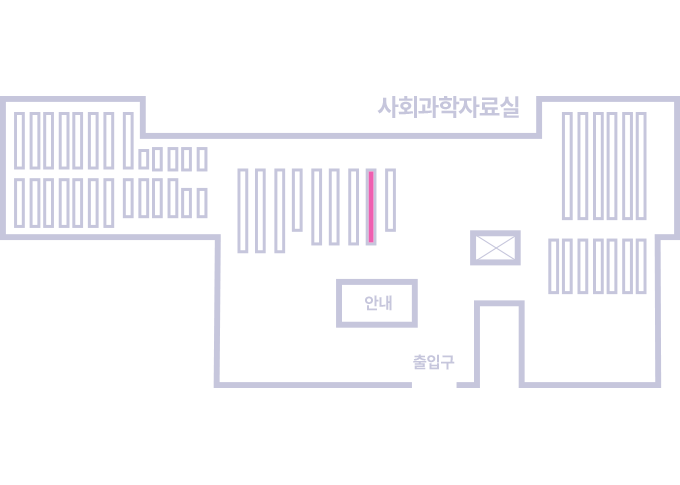

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.